Women of Achievement

1991

COURAGE

for a woman who, facing active opposition,

backed an unpopular cause in which she deeply believed:

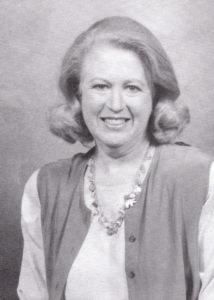

Rita Underhill

In 1985, at a time when few people understood or even knew about the disease, Rita Underhill learned that her younger brother Max had AIDS.

He called from New York to tell her and to ask that she not yet tell their family. Rita was stunned. For over a year and a half she kept the sadness and concern to herself. Rather than turn her back on him, as so many have done, Rita provided her brother with the support he desperately needed. As his health declined Max at last decided to tell the rest of his family.

Rita, although a nurse, could find little information on AIDS: only a few paragraphs in a textbook and only one book in all the Memphis bookstores. She learned through underground channels that the drug AZT, an antiretroviral medication, could help AIDS patients. But in 1985 AZT wasn’t legal in the United States. So she flew to Mexico and brought back a supply for her brother.

Rita also helped him enter the first experimental clinical study in this country. At great expense Rita made countless trips from Memphis to New York City to be with Max. And in 1988 she faced his death with all the courage she could find.

But Rita didn’t stop caring about people with AIDS when Max died. Less than a year later, she took a job with the Aid to End AIDS Committee (ATEAC). Rita has spent recent years educating people about the disease. Initially, many people assumed that Rita had AIDS and refused to be near her. When some friends were hostile and couldn’t accept her work, she had the courage to give them up. Rita has conducted outreach programs to the gay, the African-American and the Asian communities, and to IV drug abusers. She speaks wherever and whenever she is asked, and last year reached 4,000 people.

With great courage, Rita Underhill daily faces the lives and deaths of people who have contracted AIDS. She brings to these interactions the same strength, love and warmth that helped her cope with her brothers’ disease and death.

Rita Underhill passed away on July 3, 2022.