Women of Achievement

1998

HERITAGE

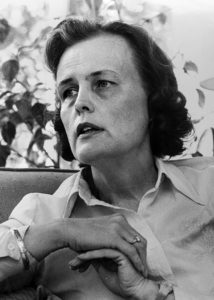

for a woman whose achievements still enrich our lives:

Lucie Campbell

Lucie Campbell, the youngest of 11 children, was born to former slaves in Mississippi in 1885. Following her father’s death, Lucie’s mother moved the family to Memphis. Lucie graduated as the 1899 valedictorian from Kortrecht High School, which was later renamed Booker T. Washington High School. She returned there to teach until her retirement.

Lucie served five years as president of the Negro Teachers Association and was vice president at-large of the American Teachers Association. In 1916, she was one of nine founding members of the Baptist Training Union Congress of the National Baptist Convention USA, Inc. Shortly after its inception, she became the national music director. She was a self-taught musician who composed more than 80 hymns, many of which she did not copyright until 1950. The majority of her compositions were given to the Baptist denomination and helped to create and maintain an atmosphere of religious fervor and optimism necessary to keep the convention intact.

In 1943, she was invited by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to attend a conference in Washington on Negro Child Welfare. She was a member of the National Policy Planning Commission of the National Education Association in 1946. Lucie was considered an accomplished and dynamic orator and was a popular women’s day speaker. Like many black professional women of her time, she devoted much of her life to others. She married the Rev. C.B. Williams of Nashville in 1960 and died there in 1973 following a brief illness.

Lucie Campbell is one of many African-Americans, and few Memphians, featured in the exhibit, “Wade in the Water: African-American Sacred Music Traditions,” which was at the National Civil Rights Museum. This exhibit, organized by the National Museum of American History and the Smithsonian Traveling Exhibit Service, opened in Washington, D.C., and traveled to more than a dozen U.S. cities.

Lucie Campbell made great contributions to a collective struggle. She was a committed and inspirational teacher, both in the academic and arts fields. She did critical community work within her profession that aimed to improve opportunities for teachers and students. She worked diligently to inspire people and to shape a musical tradition that spoke to the spiritual side of a people doing the daily and necessary work of resisting oppression, building family and community institutions that would enable them to take the struggle to another level, and openly challenge a system of inequality and injustice.