Women of Achievement

1994

COURAGE

for a woman who, facing active opposition,

backed an unpopular cause in which she deeply believed:

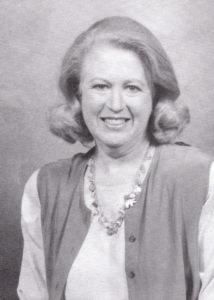

Georgia King

Georgia Anna King has walked through hurricanes, disregarded barricades on the steps of our nation’s capital, and captured microphones from guards to give voice to the homeless.

In 1989, she was one of the leaders of the Southern contingency of the New Exodus Walkers. Her group walked more than 250 miles from Roanoke, Virginia to the steps of the capital to make the plight of the homeless a priority in Congress. Queen Akua (her African name means Sweet Messenger) led the group in greeting disapproving observers with “Praise the Lord.” Before reaching their destination, skies turned black, winds arose and rain pored down. But the spirit of God told Georgia to put on her sanctified sneakers and to continue. Putting her fear behind her, she led her group forward through what was Hurricane Hugo.

Ahead on the march she saw a man who in her words looked like “one of her children.” She shouted, “Are you homeless?” “Yes,” he replied. “Then come with us to Washington. We’re going to shake the Bust to get money restored to help you.” And one more joined the group.

That year $250 billion designated for programs to help the homeless had been cut from the national budget. Upon reaching D.C., marchers from the South met marchers from the North and busloads of activists from all over. The group now was over 200,000 strong when it reached the Capitol steps. Their efforts paid off and funds were restored.

This struggle is nothing new. Georgia Anna has been fighting on behalf of the homeless since 1960. That summer she went to New York and saw for the first time people trapped by homelessness. The daughter of a Union City, Tennessee entrepreneur, she had never seen people sleeping on the streets before. Driving through the Bowery with an old family friend, she kept questioning what she saw. And she didn’t like the answers she got.

So, at the age of 20, rescuing the homeless became one of her personal missions. Queen Akua’s efforts don’t end with the homeless. She’s a grassroots activist who work directly with the mentally ill and the chemically dependent. Her interests include the arts and work on the board of Africa in April as well as with Project 30,000 Homes. She’s been honored for more than 53,000 hours of community service. Currently she’s working to open the Miracles Mission for the Homeless on South Main Street. Her goal is to look for long-term solutions for problems.

“I plant seeds,” she says of her many interests and accomplishments. “And find my courage and direction from the Lord.”

Georgia is now known as “Mother King” and is one of Memphis’s biggest activists. She founded the Memphis Bus Riders Union in 2012 in order to monitor the MATA. In 2018 she was honored with the MLK 50 Award for Leadership and Activism in the Memphis community.

Georgia Anna King passed away on February 7, 2023.