WOMEN OF ACHIEVEMENT

2011

HERITAGE

for a woman whose achievements still enrich our lives:

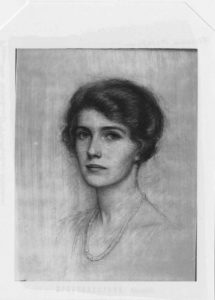

Louise Fitzhugh

Best known to many as the author and illustrator of the well-loved children’s classic, Harriet the Spy, Louise Fitzhugh leaves a lasting legacy through her groundbreaking depictions of children that challenged sex role stereotypes long before such issues had become part of the public consciousness. Her books, first published in the early 1960s, depict a range of characters — from spunky girls who aspire to be writers and scientists to sensitive boys who want to be dancers rather than lawyers. Her characters provide positive role models for any child, girl or boy, who dares to be “different.”

Louise Fitzhugh was born in 1928 to a prominent Memphis family. She began both writing and drawing when she was young and continued to do both her entire life. She attended Hutchison, Southwestern, Florida Southern College, Bard College and NYU. She was uncomfortable with both racist and sexist attitudes prevalent in the south during that time so made a conscious effort to leave her southern accent behind. Prior to her work as a children’s author, she was a successful visual artist and illustrator. Later her book, Nobody’s Family is Going to Change, was adapted into a Tony-award winning play, “The Tap Dance Kid.” Yet it is for her children’s books that she is best remembered.

Her young, quirky outsider characters offer support for children who feel awkward or insecure. This is particularly true for young lesbian and gay readers, who find reassurance in Fitzhugh’s sensitive depiction of butch girls, artsy boys, and intense same-sex friendships. Fitzhugh’s characters challenged prevailing assumptions about sex roles in ways that are both provocative and entertaining and accessible for both children and adults. Her books were essential forerunners in the movement to publish non-sexist children’s books.

In 1964, Harriet the Spy was published. The groundbreaking novel featured a rude, incredibly inquisitive heroine who threw tantrums, mocked her parents, and alienated her classmates with her obsessive note-taking and candid opinions about their personal habits. She also happened to be extremely funny. The book was an instant hit with kids, though not with all adults.

Louise Fitzhugh’s unsentimental portrait of Harriet paved the way for writers like Judy Blume to present contemporary children grappling with hitherto unmentionable problems. Harriet the Spy is still in print and continues to influence and entertain young readers.

Awards for her work include a New York Times Outstanding Books of the Year Award, an American Library Association Notable Book citation and a New York Times Choice of Best Illustrated Books of the Year.

Louise Fitzhugh died in 1974 in Connecticut at the age of 46, but her work lives on to enrich all who turn the page.