Women of Achievement

1996

HERITAGE

for a woman whose achievements still enrich our lives:

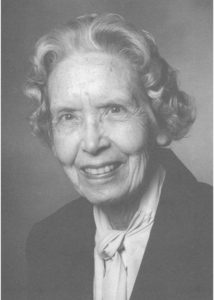

Marion Griffin

Marion Griffin was not only the first woman licensed to practice law in the State of Tennessee, she was also the first woman elected to the Tennessee General Assembly.

“Miss Marion” was born and raised in Greensboro, Georgia, but began her legal career in Memphis as a legal stenographer in the office of Judge Thomas M. Scruggs. She read law under Judge Scruggs, presented herself for examination of her knowledge of law to both Chancellor DeHaven and Circuit Court Judge Estes, was found eminently qualified to practice law by both of them and was so certified on Feb. 15, 1900.

It was the custom then and for many years afterward for an aspirant to the legal profession to study law under the tutelage of a practicing lawyer who, when he thought the aspirant sufficiently knowledgeable, referred him to a sitting judge of the local Circuit Court and to a sitting chancellor of the local Chancery Court. The judge and chancellor in turn tested the professional competency of the aspirant for admission to the bar. The Tennessee Supreme Court then issued a license to the aspirant and he was free to practice law throughout the state.

Although Marion was properly certified by two sitting judges of distinction as ready for admission to the bar, and although she petitioned the Tennessee Supreme Court in both 1900 and 1901, she was twice barred solely on the basis of her gender.

She then enrolled in the School of Law of the University of Michigan and in 1906 earned the degree of Bachelor of Laws. She was one of only two women in her class at the University of Michigan Law School. She would have preferred to enroll at the School of Law at the University of Virginia where members of her family had gone, but it did not accept women at that time or for many years thereafter.

Fortified by certification from two sitting judges and a law degree from one of America’s pre-eminent law schools, either of which would have been sufficient to get a male admitted to practice law, Marion Griffin then began the process of energizing the Tennessee Legislature to pass an act giving women the right to practice law in the jurisdiction. At first she was, in her words, “greeted with wisecracks and guffaws,” but she persisted and ultimately the bill was passed on Feb. 13, 1907 and approved by Governor Malcolm Patterson on Feb. 15, 1907.

On July 1, 1907, Marion Griffin became the first woman admitted to practice law by the Supreme Court of the State of Tennessee, and was sworn in and enrolled as a member of the local bar.

She practiced law in Memphis for more than 40 years from an office located variously on Main Street, on Court Avenue and for many years in the Goodwyn Institute Building on the southwest corner of Third and Madison, the present site of the First Tennessee Bank building.