Women of Achievement

2004

HERITAGE

for a woman whose achievements still enrich our lives:

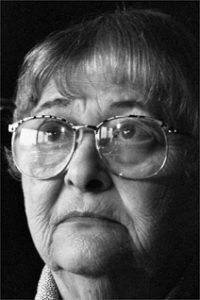

Eleanor “Dicky” Ehrlich

Eleanor “Dicky” Weile Ehrlich never stopped feeling lucky that she survived nine different German concentration camps.

So she never stopped teaching about the Nazi Holocaust. ‘‘There is too much to tell,’’ Dicky said. ‘‘There is so much yet not told. Just remember, it all did happen … and please keep it from happening again.’’

Dicky began life in Berlin where her mother owned a needlework shop and her father was a traveling manufacturer’s representative. As Hitler’s restrictions and persecution of Jews intensified, she and her parents moved in 1933 to Amsterdam where Dicky became a neighbor and sometime playmate of Anne Frank.

But soon the Nazis ended Holland’s 100-year neutral history by marching in with occupation soldiers. Eight times Dicky answered the door late at night to find Gestapo soldiers there. Eight times she talked or sang to them and they went away. A ninth time she didn’t awaken until two soldiers were looming over her bed.

The Weile family was loaded onto cattle cars to a camp in southern Holland. It was February 1943. The family was separated. Within eight months, her mother Tilla, who was assigned to tend to young children in the camp, caught scarlet fever. With only aspirin and sulfur available as medicines, Tilla died in November and was cremated. Dicky never forgot the smell of the smoke that blew over her as her mother’s body was incinerated.

Meanwhile, the Philips Company had persuaded the Germans to build in the camp a factory which would keep Dutch Jews in Holland as long as possible at a time when Jews from all over Europe were being shipped to death camps in Germany and Poland. Dicky always believed it was her training to build intricate radio tubes for V1 and V2 rocket weapons that delayed her departure to Auschwitz for a critical 10 months and saved her life. She was convinced that if she had arrived sooner, she would have been gassed with thousands of others.

Dicky reported with pride that she and her fellow inmates were able to damage about 60 percent of the instruments they made, without being detected, assuring that many of the German rockets never reached their mark.

In June 1944, she was shipped to Auschwitz, Poland, where three large chimneys turned the night sky orange and the stench of burning flesh was unreal. Though it was a while before she knew it, Dicky arrived in the notorious camp on D-Day, June 6. Her hair clipped short, number 81020 tattooed on her left arm, she was soon loaded on cattle cars again, bound for Reichenback in east Germany. She was moved four more times as the Germans dodged advancing Allied forces and kept the inmates manufacturing parts.

Finally, she arrived near Hamburg for the hardest work yet – shoveling mud to dig tank traps, ditches three yards wide and three yards deep, shaped like a V. Guards stood above, snapping whips to speed the exhausted workers.

Dicky was barely holding on. Fortunately, the Swedish Red Cross made a deal with Hitler to trade some concentration camp prisoners for German deserters. Dicky was on the second transport to Sweden. It was three days before the end of the war. She was 23 years old and weighed 88 pounds. She had spent over 2-1/2 years in nine concentration camps. She later learned that her father had been killed in the Auschwitz gas chamber on Oct. 1, 1944.

In 1948, she agreed to move to Atlanta to live with an aunt. Her ship arrived in the New York harbor as July 4 fireworks blasted. She met and married Sidney Ehrlich and began life as a wife, mother of two children and unstoppable public speaker. She became a deeply patriotic American who always flew a giant flag on Independence Day.

Wherever she lived in the United States, Dicky shared her story. She also taught teachers how to teach about the Holocaust: ‘‘To teach this to young people and to impress upon them how very lucky they are to live in this country with all of its freedoms, we must dig a little deeper – what does it do on a personal basis when all the freedoms we take for granted are taken away?’’

She described the forced walk of 2,000 inmates and 3,000 cows through snow for six days with paper shoes to wear and one slice of bread and snow to eat. She told about a trip that should have been three hours that went on for 11 days and nights, standing in a freight car with 209 other prisoners with three pieces of bread, no water and no modesty when allowed under a stopped train car to ‘‘use the bathroom’’ at gunpoint.

In 1997, she was interviewed and videotaped for Steven Spielberg’s Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation. Dicky Ehrlich died in Memphis on May 1, 2001. She was 78.

Friend and colleague Rachel Shankman, regional director of Facing History and Ourselves, said, ‘‘No one who ever met her will ever forget her. What made her special to the children and teachers was her ability to bring that hard history to life, and talk about it with humor and resiliency.’’

A teacher who heard Dicky speak in Arkansas several years ago wrote a two-page letter expressing the power of Dicky’s testimony in changing her life. ‘‘I know that I will move through the world differently now. I hope that I will be a better person. I believe that what you have done here is to become a rescuer. Somehow, some way, your words continue to make me grow.’’