Women of Achievement

2008

HERITAGE

for a woman whose achievements still enrich our lives:

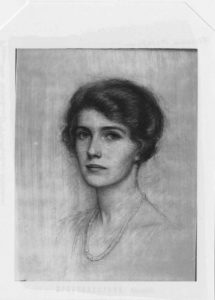

Florence McIntyre

The beloved Memphis College of Art Professor Emeritus, Burton Callicott wrote, “A pure truth throughout my years has never ceased to strike me with enormous force is that but for McIntyre’s zeal and initiative, there would be no Memphis College of Art in the city today. The seed which sprouted and grew into Memphis College of Art was planted by Florence McIntyre in 1914.”

Born in 1878 into a prominent Memphis family, Florence McIntyre dedicated her whole life to the making and teaching of art to mid-southerners no matter what the circumstances.

After her education in Memphis, Miss McIntyre studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, attended classes of William Merritt Chase in Philadelphia and spent several summers at the artist’s colony at Woodstock, NY. Her extensive travels brought her into contact with many artists and exhibitions.

In July 1914, she invited prominent women to organize the Memphis Art Association. The first exhibition was held at the Nineteenth Century Club in November of that year. Memphians got to see works of Ralph Blakelock, Winslow Homer, George Inness and other famous artists of the time. Memphians’ interest in art began to grow.

Mrs. Bessie Vance Brooks, Woman of Achievement for Heritage in 2014, donated money in memory of her husband Samuel Hamilton Brooks to build an art museum in Memphis. With no other funds available, the Memphis Art Association became the first support group for the Brooks Museum. Florence McIntyre with her broad experience and education was hired to be the first director and the first exhibition opened there July 10, 1916.

Life in the art world is often complicated and political. There developed a disagreement between one art patron who wanted a $50,000 memorial to her husband to be placed on the Parkway, while another patron objected to having it located opposite his home. Florence McIntyre was caught in the middle of the dispute, which resulted in Abe Goodman, the chairman of the Brooks Art Gallery, being replaced and Miss McIntyre resigning in 1922 after six years as the first Director of the museum.

McIntyre’s unemployment didn’t last long. Her childhood friend and neighbor, Rosa Lee, asked her to become the director of the Free Art School then meeting at the Nineteenth Century Club. The enrollment grew so fast Miss Lee deeded her house at 690 Adams to the city in 1929 and later purchased the Woodruff-Fontaine house and repeated her generosity. Later the stables of the two houses were joined together in 1931 to make room for more classes. The school came to be known as the James Lee Memorial Academy of Arts and the enrollment grew to 700 students.

Through McIntyre’s leadership the program of art offerings grew from drawing, painting and sculpture to include crafts: batiks, pottery, metal and jewelry work. Departments of design and interior decoration were added. The stable became home to the performing arts named The Stable Playhouse. The school became an important civic enterprise and many graduates went on to become well known artists around the nation.

In 1935 controversy returned. Miss McIntyre hired George and H. Amiard Oberteuffer, a husband-and-wife team from Philadelphia to teach. With them came a spirit of modernism that she could not control, and dissention arose. During this time Miss Rosa Lee died and the split grew. Burton Callicott who taught at the school said, “In the spring of 1936 a schism occurred. The split was totally vertical: the Oberteuffers and other teachers, some Board members and some of the students left and founded a new school, The Memphis Academy of Arts (now Memphis College of Art).”

In spite of this Miss McIntyre continued her school at the Lee House until 1942 when Robert Lee died and the support of the Lee family stopped. But that didn’t stop her dedication; she then moved her classes across the street to her own home and kept the school going for 20 more years until her death May 15, 1963 at age 84. She taught art for 40 years to more than 10,000 Mid–Southerners.

Callicott, who was part of those who left with the modernists, says Miss McIntyre never spoke to him again but he is emphatic that Florence McIntyre should be honored. Mr. Callicott said, “There should be a memorial to Florence McIntyre. For many years, Florence McIntyre was art in Memphis.”