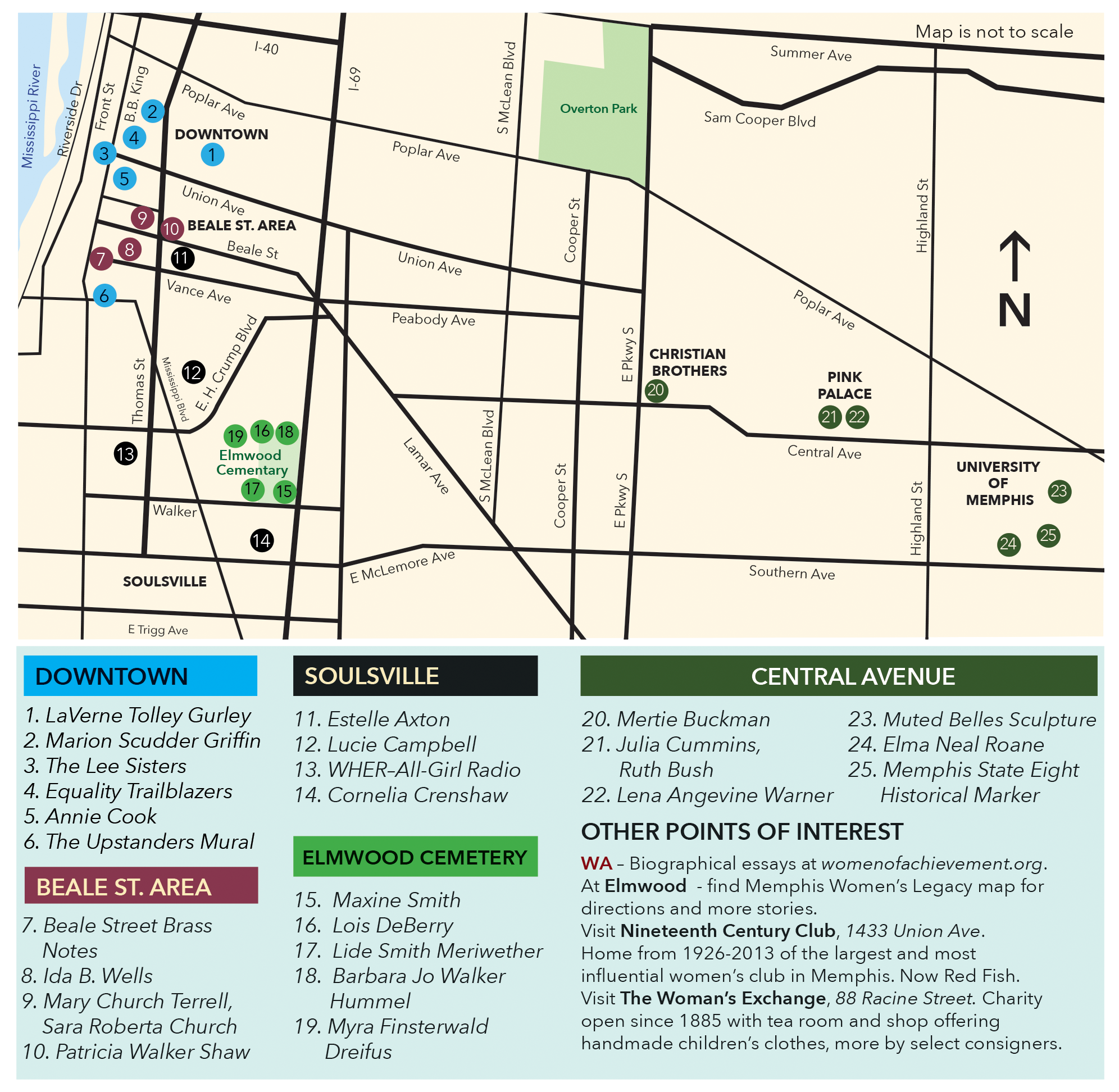

CENTRAL AVENUE

20. Mertie Buckman – (1904-1999) Sculpture in Buckman Hall. Used her considerable resources to improve human rights and impact social issues. She campaigned for water fluoridation, advocated for a library for the Raleigh community, gave seed money to launch the Women’s Foundation for a Greater Memphis, endowed Rhodes College and Girls Inc. Sculpture is titled “Essence of Mertie.”

21. Julia Cummins – (1869-1959) Mansion Mezzanine. Hired by the Parks Commission as the first “Superintendent and Hostess of the Museum of Natural History and Industrial Arts.” Cummins kept the galleries and grounds clean and maintained the museum’s records. Cummins did not abide children and had porters show “Quiet in the Museum” cards to visitors who were noisy or talkative. Ruth Bush (1897-1993), succeeded her as director in 1950 particularly because of her ability to work well with children. She started educational programs, supported the Junior League in creation of the Youth Department room and sponsored field trips to places like Shelby Forest.

She retired in 1967 after a 45-year career with the Parks Commission.

22. Lena Angevine Warner – (1865-1948) In Saddlebags to Science exhibit. Was a pioneer in professionalizing nursing, designer of the first nurses’ uniform and a tireless fighter for better sanitation and public health. Warner lost most of her family to Yellow Fever and when it became the leading cause of death in the Spanish-American War in Cuba, she volunteered her services because she had acquired immunity to the disease. She worked closely with Reed Commission doctors who, with brave volunteers, discovered that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitos.

23. Muted Belles Sculpture – In public plaza in front of the University of Memphis Art Museum. A monument to Memphis women, dedicated in 1994. Artist Gail Rothschild says the sculpture’s shapes are a cross between bells and hoopskirts. These bells/belles were selected to reimagine the stereotype of the Southern belle and represent themselves and other women who are muted by a historical record that ignores them. Remembered are Women of Achievement recipients Annie Cook, Ida B. Wells, Alberta Hunter, Myra Dreifus, as well as:

Frances Wright (1795-1852) In 1825 founded Neshoba Community where blacks and whites worked side by side. After Neshoba failed, she continued to advocate for universal freedom. WA

Julia Hooks (1852-1942) Founded a private school and a music academy to give African American children opportunity to learn. The “Angel of Beale Street” also worked selflessly for the poor.

Susanne Coulan Scruggs (1864-1945) Advocate for children, she founded the Memphis Playground Association, Juvenile Court and worked to improve public education.

Juanita Williamson (1917-1993) LeMoyne-Owen professor gifted in both teaching and scholarship, known especially for her research on the impact of speech patterns on learning.

24. Elma Neal Roane – (1918-2011) Roane led the struggle for women’s rights in athletics in local, regional and national settings for four decades, helping change forever the treatment of female athletes. She began her teaching career at Treadwell High School. In 1946 she joined the Memphis State College faculty, where she ultimately held the position of director of the

Women’s Division, Physical Education Department, and coordinator of MSU Women’s Athletics. In those positions Roane fought for the rights of women students to have funding, space, equipment, publicity and support equal to male athletes.

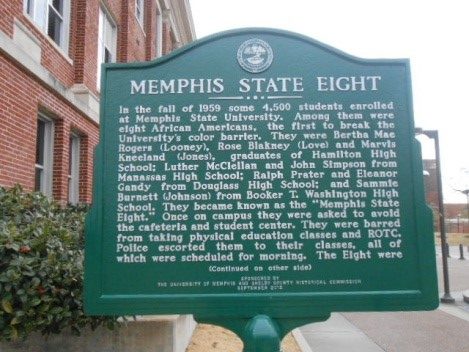

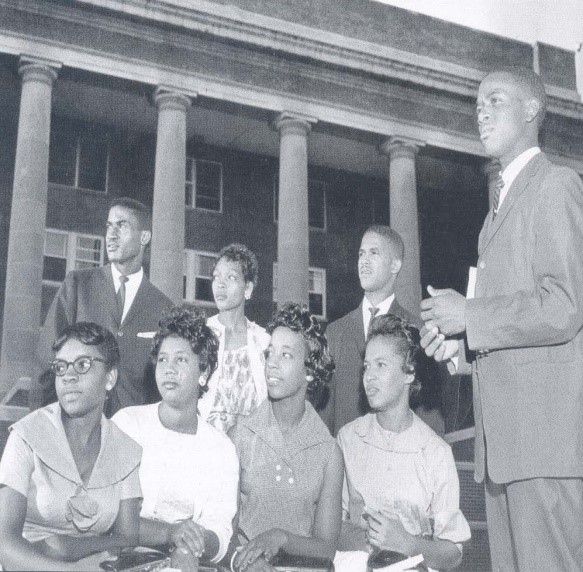

25. Memphis State Eight Historical Marker – Marker On Alumni Avenue north of Walker. In the fall of 1959 eight African Americans enrolled at Memphis State University, the first to break the University’s color barrier. The group included five young women: Bertha Mae Rogers (Looney), Rose Blakney (Love), Marvis Kneeland (Jones), Eleanor Gandy and Sammie Burnett (Johnson).

Downtown

Beale Street Area

Soulsville

Elmwood Cemetery

Central Avenue